Building a web app - Introduction

During my work at Edinburgh Genomics, I had my first foray into web development. Due to the huge numbers of samples we deal with, we needed a way of viewing all of the metadata we were generating in a better way than pasting tsv content into the local wiki, as we were doing initially. Static sites like blogs and wikis are all very well, but reporting on all of the hundreds of samples passing through our pipelines would require a dynamic website powered by a database and web server.

Architecture

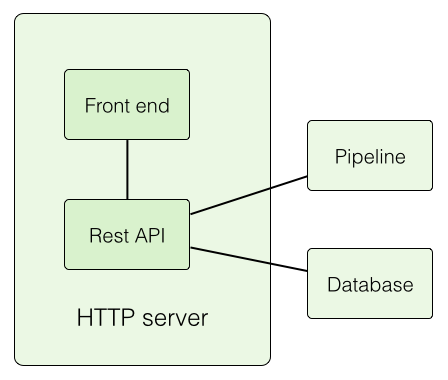

First, we had to consider the overall architecture of this new Reporting App. Our data processing pipelines would push data to a database, which would then be queried by a front-end web app and displayed. We could have gone with this simple two-piece architecture, but we decided to add a third layer: a Rest API on top of the database. Apart from being something of a fad nowadays, a Rest API provides a useful layer of control on top of the database, as well as a convenient and securable HTTP interface for pushing and pulling content.

Web app layout. The codebases for the Rest API and the front-end sit inside of an HTTP server, with the Rest API communicating with a database as a back-end and our pipeline as a client.

Next, we had to decide what each of these layers should be implemented in. We decided to use a Python web framework for the front end, since we're mainly Python programmers. We could have gone with Django, but in the end we decided on Flask as a simpler, more lightweight alternative.

For the database, we decided to use MongoDB, a NoSQL database with powerful aggregation features. Searching for a Python-based NoSQL Rest interface, we decided on Eve which, by coincidence, is built on top of Flask. We could have gone with a SQL database (and we might move to one later) but went with NoSQL because we knew we would be collecting more and more types of data as time went on, and NoSQL, storing JSON rather than tables, is essentially schema-less. Having said that, we did use Eve to add a layer of data validation for content entering the database. This way, we could have an extremely flexible and extensible database to which we could add new fields and endpoints without having to migrate the whole thing over to a new schema each time we updated.

Finally, we had to run the thing somewhere. Initially for development, we could use Flask's own internal Werkzeug server. However, to run a shared instance of the app for access by many people, we needed something a bit more elaborate. With a short script, we were able to run the app on Tornado, a Python-based (can you see a theme developing?) web server like Werkzeug, but a bit more production-ready.

As for hosting, we already had an unused Linux VM on our network, so we decided to open a couple of ports to our internal network and set it up as a web server with a few Bash scripts for configuring, starting, stopping and restarting the app. There'll have been better, more reliable ways of doing this, but I usually find that rolling your own solutions to problems teaches you a lot and helps you understand how everything works if/when you move to third-party solutions. This was exactly what happened when we decided to switch web servers from Tornado to Apache - once the initial Apache head scratching was out of the way, prior knowledge of the interplay between Python and the webserver via WSGI was hugely helpful.

The series

This will be a multi-part series on how the Edinburgh Genomics Reporting App was built. It's by no means a perfect example of web programming, but it's continuing to get better as we develop it, and I have learned a lot from the process.

- Part 1: Building a Rest-powered database with NoSQL and Eve

- Part 2: Building a Flask front-end

- Part 3: Setting up Flask apps on Tornado

- Part 4: Setting up Flask apps on Apache with mod_wsgi

External links

-

Full Stack Python: http://www.fullstackpython.com

A very useful website for all aspects of Python web development.